What is NCL?

Late Infantile Neuronal Ceroid Lipofuscinos (Li-NCL) or CLN2, is part of a group of genetic neurodegenerative lysosomal storage disorders that are sometimes grouped together and called Batten’s Disease. An error in the genetic code causes proteins to be made incorrectly in such a way that the lysosomes (waste removal) cannot break them down properly and transport waste from the cell. This eventually causes the cell to stop working or die. Essentially, the garbage can of the cell gets too full, and then there is nowhere for the waste to go.

Carling and Colton's parents always referred to the disorder by the name of the specific form that they had—Late Infantile NCL, since Batten's is actually CLN3 or Juvenile NCL. The issue resulting in Li-NCL is found on chromosome 11, which has an estimated 2,000 different genes on it. The gene affected is the CLN-2 gene. A simple way to zoom into the source of this disorder is to remember:

- We each (normally) have 46 chromosomes, 23 pairs (one from each parent x 2).

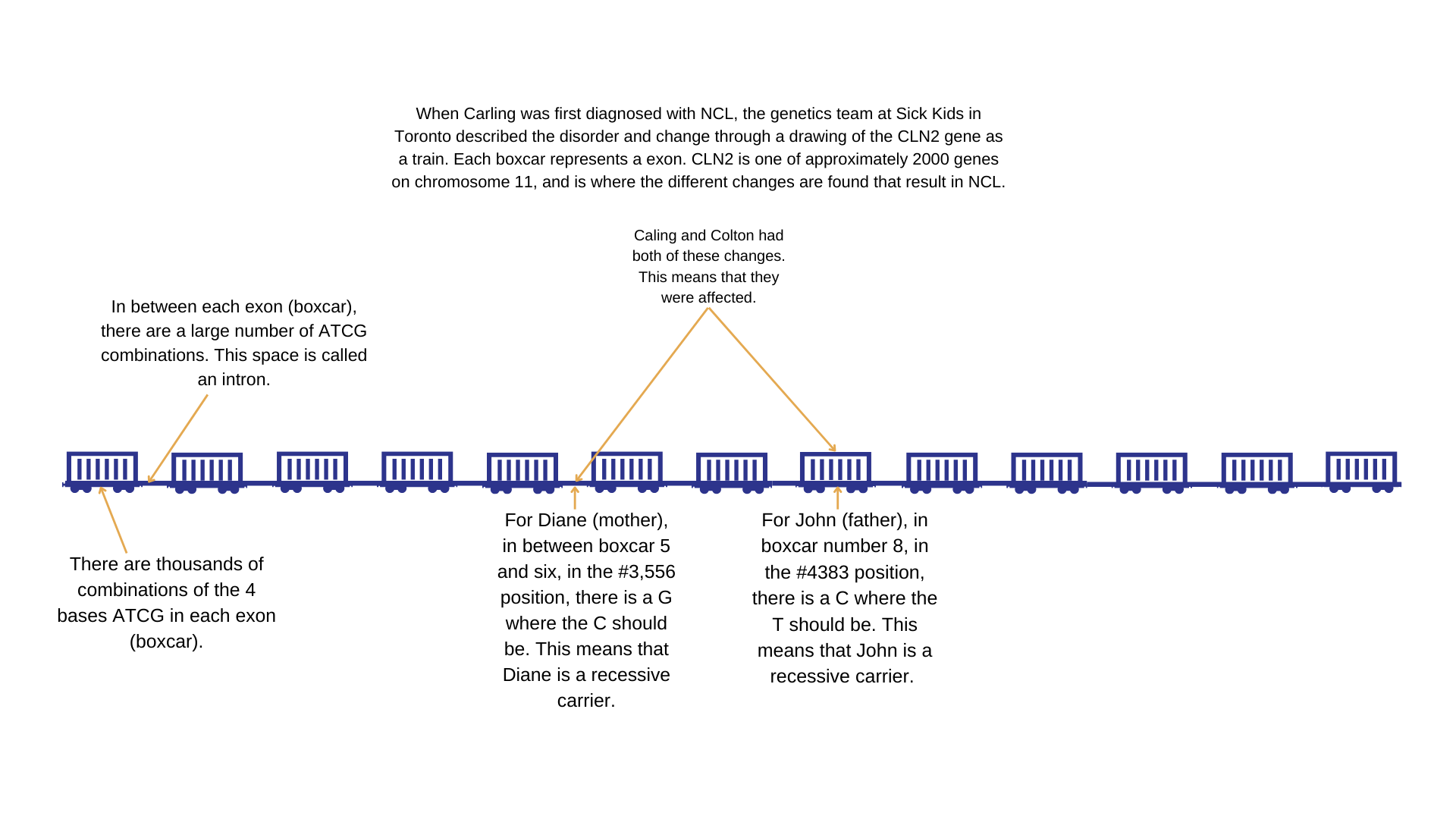

- On the Chromosome 11 there are 2,000 different genes (think of these as trains with boxcars and connectors between them). So, 2,000 trains on Chromosome 11.

- One train (gene) is called CLN2. It has 13 boxcars (exons) and 12 sections linking the boxcars (introns).

- Each boxcar and link between them has thousands of combinations of the 4 bases that make up DNA (genetic instructions). These are shortened to the letters A, T, C, and G. In every combination /position they have a specific place/order that make things work.

- When a letter is out of position, it is called a change.

- If there is one change in any place (boxcar or connector) on the CLN2 gene, a person is called a carrier.

- If there are two changes in any place (boxcar or connector) on the CLN2 gene, a person is affected with Li-NCL.

- Changes are only passed along genetically. They are not something that just "happens."

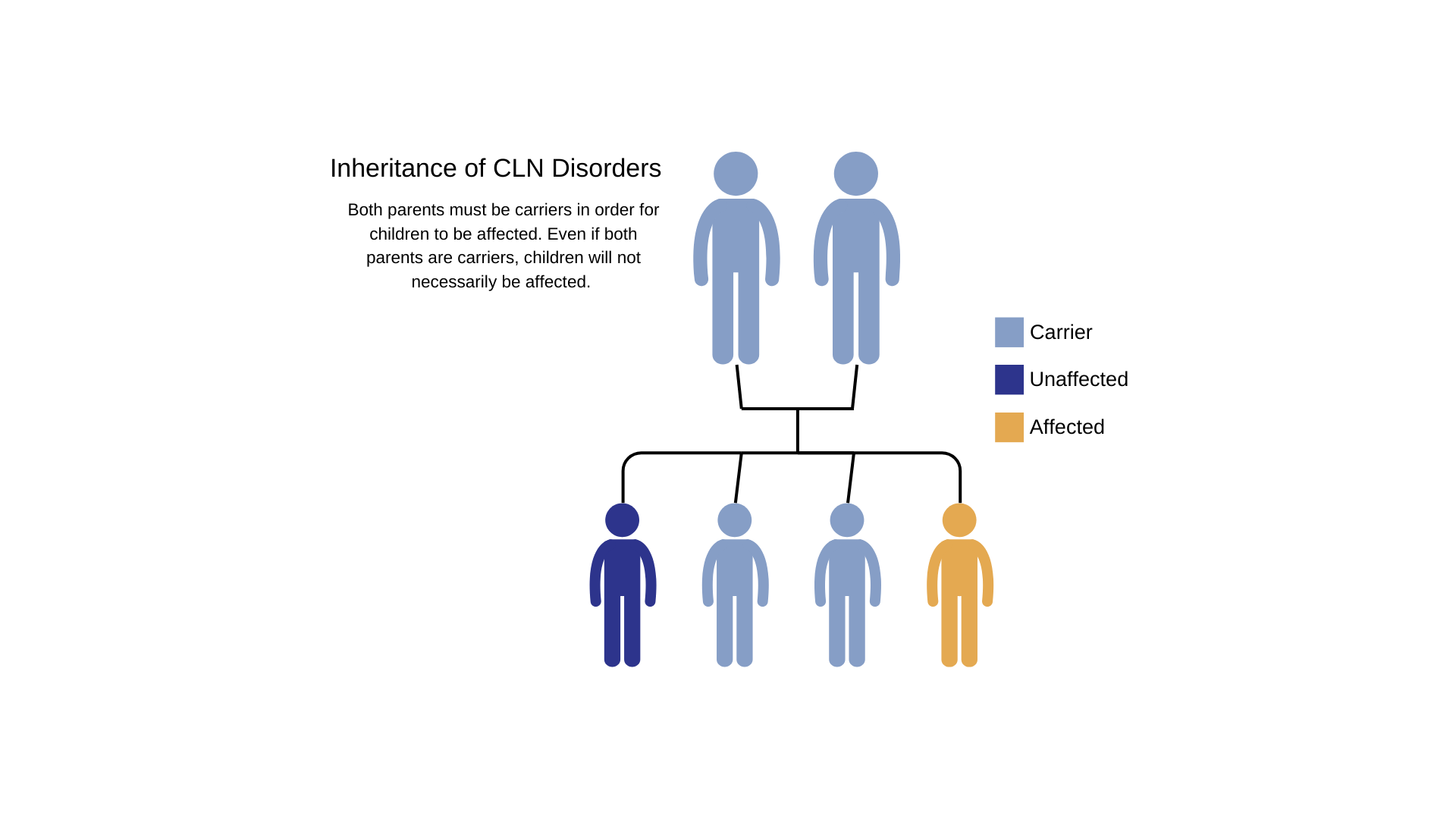

NCL is a degenerative neurological disorder. It is genetic and both parents must be carriers for a child to develop NCL. Over time, affected children suffer mental impairment, worsening seizures, and progressive loss of sight, motor skills, and verbal communication.

NCL is typically diagnosed by a neurologist who will perform a variety of tests, ranging from least to most invasive. Many tests are done prior to eliminate other possible diagnoses. To confirm NCL, the tests often include: blood and urine tests, skin biopsies, conjunctive tissue eye studies, EEGs to detect seizure activity, and brain scans (such as CT or MRI).

There are many different forms of NCL, and more continue to be discovered. Four main types of NCL are:

Infantile NCL (CLN1, Santavuori-Haltia disease) begins between about 6 months and 2 years of age and has a life expectancy of 6 to 10 years.

Late Infantile NCL (CLN2, Jansky-Bielschowsky disease) begins between the ages of 2 and 4. Its average life expectancy is 9 to 11 years.

Juvenile NCL (CLN3, Batten Disease) begins between the ages of 5 and 8 years of age. Those affected by it usually live into their late teens or early twenties, although some have survived into their thirties.

Adult NCL (CLN4 or 5, Kufs or Parry's Disease) generally begins before the age of 40. While the life expectancy varies, the disorder does shorten life expectancy.

NCL is relatively rare, occurring in an estimated 2 to 4 of every 100,000 births in North America. The disorders have been identified worldwide, although they appear to be more common in Newfoundland, and in Finland, Sweden and other parts of northern Europe. Although NCLs are classified as rare diseases, they often affect more than one person in families that carry the defective gene.

NCLs are autosomal recessive disorders; that is, they occur only when a child inherits two copies of the defective gene, one from each parent. When both parents carry a defective gene, each of their children faces a one in four chance of developing NCL. At the same time, each child also faces a one in two chance of inheriting just one copy of the defective gene. Individuals who have only one defective gene are known as carriers, meaning they do not develop the disease, but they can pass the defective gene on to their own children.

Adult NCL may be inherited as an autosomal recessive (Kufs) or, less often, as an autosomal dominant (Parrys) disorder. In autosomal dominant inheritance, all people who inherit a single copy of the diseased gene develop the disease. As a result, there are no unaffected carriers of the gene.

It has been many years since this family was the midst of the science, research, development of treatments and discoveries. Much has changed. These stories share this family's perspective of the time. The hope is that they are still valuable to give a glimpse of where things were when they were an active special needs family.

For anyone who has a relative identified with NCL, (or any genetic disorder for that matter), you may be interested in finding out if you are a carrier. Please be aware that this can be done as part of family planning. For NCL relatives, you would ask your doctor about having a specialized genetic blood test done to identify if you are a carrier. Remember, even if you are a carrier - you will not develop the disorder, once you have past the age of onset. Both parents have to be carriers to develop this condition. Identifying if someone is a carrier, will help determine if further testing on the carrier's partner should be considered, again, as part of family planning.

It is not rude to ask a family member who has a genetic disorder what the specific genetic condition is as part of future generations planning a family. It is simply gathering information for better health resources for both the relatives and their health practitioners. More information is always better.

If you reading this and are related by blood to either John or Diane

John's (maternal) side of the family:

If you are related to John, have them check if Exon 8 has a T to a C change at positon #4383 on the CLN2 gene.

Diane's (maternal) side of the family:

If related to Diane, have them check Chromosome 11 for Intron 5: G556C on the CLN2 gene.

The results of this test will only determine whether or not you are a carrier. This is a rare disorder. The chance that both parents are carriers is slim.